Designing for Understanding Through Multiple Representations

- Role of Representations in Mathematics Education: Representations like models, equations, and diagrams are essential for understanding abstract mathematical concepts, significantly enhancing comprehension.

- Benefits of Multiple Representations in Teaching: Using a variety of representations in math education leads to improved mathematical performance, faster concept acquisition, and enhanced problem-solving skills.

- Design and Application of Representations: The effectiveness of representations relies on intentional design and appropriate application, requiring clear conveyance of both general messages and specific mathematical concepts.

- Strategies for Effective Representation Use: Ensuring effective use involves understanding the context of representations, noticing important features, and transferring knowledge to new problems.

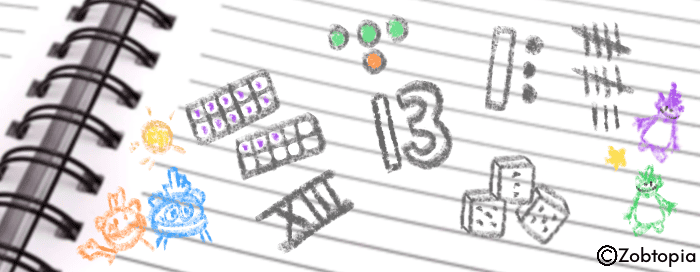

A Brief History of Numbers

Throughout history, different societies have developed unique ways to represent numbers, each reflecting their unique cultural, practical, and scientific needs.

The ancient Egyptian system was based on hieroglyphs. The Babylonians used a combination of two symbols in various counts to express numbers. The ancient Greeks primarily used an alphabetic numeral system, where each letter of the Greek alphabet was assigned a value. The Roman numeral system was based on combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet (I, V, X, L, C, D, M) to represent numbers. The Chinese developed a decimal system where numbers were written in vertical columns. The Mayan civilization used a combination of dots, bars, and a symbol for zero.

Representing the Abstract

In short, numbers are abstract entities whose expression is typically made concrete through some kind of visual representation so that people can make sense of and from numbers.

Representations Support Math Learning

Research into the use of representations in mathematics education shows that representations significantly enhance comprehension of abstract mathematical concepts [1], and multiple representation-based instruction generally leads to improved mathematical performance [2].

A study of 91 eighth-grade students from four middle school classes compared the effectiveness of single versus multiple representations [3]. The study found that the multiple representations group learned the concepts faster, exhibited better mathematical, conceptual understanding, and demonstrated higher-level problem-solving skills compared with students exposed to a single representation.

Multiple representations have also been shown to enhance aspects of creativity in mathematical problem-solving, including fluency, flexibility, and originality [4].

Levels of Meaning in Representations

Despite their general effectiveness, representations must be intentionally designed and applied if they are to be useful to students [1] [2].

Making sense of representations requires that students understand both the overarching message each representation aims to convey as well as the specific concepts each embodies [5]. Without appropriate guidance, students can misinterpret the representations and fail to develop the requisite content knowledge [6].

In other words, representations help students make sense of concepts only if students can make sense of the representations!

Making Representations Make Sense

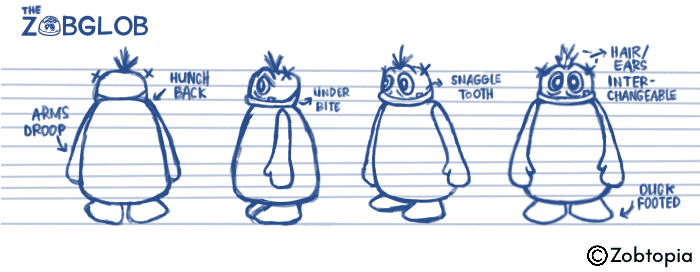

For our app, we addressed the major challenges to the effective use of representations in mathematics education. Overall, we designed our representation strategy to help students understand the meaning of the representations we use, notice the key concepts within the representations, and transfer the knowledge gained from the representations to new problems.

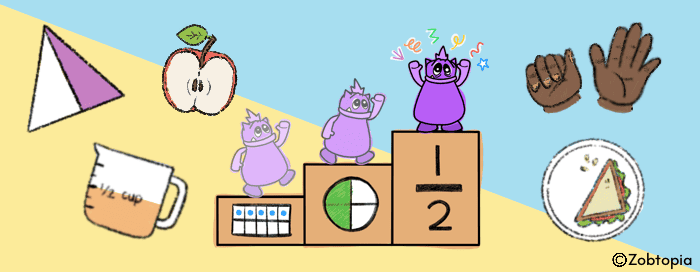

Challenge 1: Understanding

For students to make sense of representations, they must first understand the overall context of the representation, including its essential form, how the form is meant to function, and the language associated with the form.

Number is represented in our culture in five major ways: as a group of objects, a dot-set pattern, a position on a line, a position on a scale (e.g., a thermometer) and a point on a dial. In each of these contexts, number is also talked about in different ways, with a larger number (and quantity) described as “more” in the world of dot-sets, as “further along” in the world of paths and lines, as “higher up” in the world of scale measures, and as “further around” in the world of dials. Children who are familiar with these forms of representation and the language used to talk about number in these contexts have a much easier time making sense of the number problems they encounter inside and outside of school [7].

In our app, we leverage multiple differentiated representations throughout the curriculum and within each lesson to support each student’s unique understanding. Because the type of representation used affects the effectiveness of it, we use representations that are intentionally aligned with the concepts being taught, the target age range, and the overall teaching strategy for the lesson [1] [2].

Challenge 2: Noticing

Next, if representations are to effectively convey meaning to students, the students must notice the important features, patterns, and relationships within the representations [8]. Through successful noticing across multiple representations, students begin to develop increasingly complex and flexible strategies for problem solving that they can then practice with and apply to novel challenges.

In our app, we leverage signaling to support student noticing. Using design strategies such as color coding, labeling, and structural organization, we scaffold noticing, assisting students in focusing on key concepts and understanding their interrelations. Additionally, by using different forms of representations, using familiar representations in novel ways, and pairing dissimilar representations, we make the representations accessible to and understandable by all learners [9], while at the same time developing students’ flexibility in making sense of representations more generally, preparing them for future learning opportunities.

Challenge 3: Transferring

Finally, for representations to serve their full purpose, students must be able to transfer the knowledge gained through the representations to new and ultimately more abstract problems. Developing this ability typically involves students oscillating between advancing and revisiting earlier stages of comprehension, a process aided by interactions with representations of varying complexities [10].

In our app, we leverage fading to support students’ abilities to transfer knowledge to new cognitive challenges [6]. This approach begins with tangible, concrete forms of mathematical concepts, such as physical models and visual depictions, making them relatable and understandable to students. Gradually, we transition these representations to more abstract forms like symbols and equations, allowing students to consolidate their understanding and apply it to new, more complex problems. This method ensures a seamless progression from concrete understanding to abstract thinking.

Representing Understanding

We appreciate the power representations have in communicating abstract concepts in concrete ways. And, we understand that for representations to work, they have to make sense to the students. That is why we have designed our representation strategy to help students make sense of and from our representations.

Connected with our intentional learning progressions, we present our representations in ways and in an order that solidifies understanding, supports noticing, and becomes increasingly less concrete and more abstract. We further use our representations and the ordering of them to introduce foundational concepts in an intuitive manner, preparing students for engagement with more complex topics. Through this process, students gain confidence in both making sense of the representations and more importantly understanding and applying the abstract concepts conveyed by them [8] [10].

References

[1] Sokolowski, A. (2018). The effects of using representations in elementary mathematics: Meta-analysis of research. IAFOR Journal of Education, 6(3), 129-152. http://iafor.org

[2] Çetin, H., & AYDIN, S. (2020). The effect of multiple representation based instruction on mathematical achievement: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 5(1), 26-36. https://doi.org/10.24331/ijere.647531

[3] Liang, C. P., & She, H. C. (2023). Investigate the effectiveness of single and multiple representational scaffolds on mathematics problem solving: Evidence from eye movements. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(6), 3882-3897. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1943692

[4] Bicer, A. (2021). Multiple representations and mathematical creativity. Thinking skills and creativity, 42, 100960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100960

[5] Van Meteris, P., List, A., Lombardi, D., & Kendeou, P. (2020). Handbook of learning from multiple representations and perspectives. Routledge.

[6] Kokkonen, T., & Schalk, L. (2021). One instructional sequence fits all? A conceptual analysis of the applicability of concreteness fading in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology education. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 797-821. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-020-09581-7

[7] Griffin, S. (2004). Building number sense with Number Worlds: A mathematics program for young children. Early childhood research quarterly, 19(1), 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.01.012

[8] Brezovszky, B., McMullen, J., Veermans, K., Hannula-Sormunen, M. M., Rodríguez-Aflecht, G., Pongsakdi, N., ... & Lehtinen, E. (2019). Effects of a mathematics game-based learning environment on primary school students' adaptive number knowledge. Computers & Education, 128, 63-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.011

[9] Bautista, A., Habib, M., Ong, R., Eng, A., & Bull, R. (2019). Multiple Representations in Preschool Numeracy: Teaching a Lesson on More-or-Less. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.17206/apjrece.2019.13.2.95

[10] Watts, C. M., Moyer-Packenham, P. S., Tucker, S. I., Bullock, E. P., Shumway, J. F., Westenskow, A., ... & Jordan, K. (2016). An examination of children's learning progression shifts while using touch screen virtual manipulative mathematics apps. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 814-828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.029